The Formula 1 world championship was born on this day at Silverstone 70 years ago.

Read how the championship was founded, and how the top two Italian teams Alfa Romeo and Ferrari led the way in 1950, in this extract taken from Peter Higham’s new book ‘Formula 1 Car by Car 1950-59’.

1950: Birth of the Formula 1 World Championship

A motorcycling world championship had been organised in 1949 and, at a meeting in the last week of February 1950, pre-war racing driver Count Antonio Brivio, the Italian delegate to the FIA, suggested an F1 World Championship for drivers. The Grandes Épreuves of Britain, Monaco, Switzerland, Belgium, France and Italy, plus the Indianapolis 500, were announced as qualifying rounds with points awarded to the top five finishers on the scale 8–6–4–3–2 and an extra point to whoever set the fastest race lap. Indy meant that the championship extended outside Europe but it had little relevance during the 11 years it was officially included.

The new World Championship began at Silverstone on Saturday 13 May 1950 with the drivers (and the top therein the F3 race) presented to the royal party by Earl Howe before the start. The race was awarded the honorary title GP of Europe and was flagged off by Brivio. A crowd of up to 100,000 paid between six shillings (general admission in advance) and £2 2s (for the main pit grandstand) to watch dominant Alfa Romeo 1–2–3. Alfa’s thirsty supercharged cars duly won the title but Ferrari exploited the larger capacity normally aspirated alternative to challenge by the end of the season.The most disappointing aspect for British fans was British Racing Motors. Equipped with a V16 engine, the Retype 15 had been unveiled amid much hype at Folkingham airfield on 15 December 1949 and founder Raymond Mays gave a brief demonstration during the 1950 British GP meeting. However, the car did not appear in a championship race and Raymond Sommer broke its transmission at the start of his heat when it finally made its début in Silverstone’s non-championship International Trophy. Reg Parnell won a couple of lesser races at a wet Goodwood in September before both he and Peter Walker retired from the non-championship season finale in Barcelona.

Goodwood apart, it had been a sorry start for Britain’s national team.

Alfa Corse (Alfa Romeo)

Emilio Villoresi led an Alfa Romeo 1–2 on the car’s début in the 1,500cc race that supported the 1938 Coppa Ciano at Livorno. The cars complied with the new Formula 1 in 1947 and they proved virtually unbeatable that year and the next. A single exhaust pipe had replaced the original small-diameter twin arrangement and triple choke Weber carburettors were fitted. However, the team was rocked by the deaths of drivers Achille Varzi (practising for the 1948 Swiss GP), Jean-Pierre Wimille (driving a Simca-Gordini in Buenos Aires’s Palermo Park in January 1949) and Count Trossi (from cancer later that year).

Alfa Romeo did not race in 1949 and its participation in 1950 was initially uncertain. In January, The Autocar noted that the team’s appearance depended ‘entirely on the financial situation of the company and… the politics of the situation.’ A three-car entry was finally confirmed in March amid talk of a government subsidy.

The engine now featured two-stage supercharging and developed 360bhp at 8,500rpm, although such was their initial dominance that revs were normally restricted to 8,000rpm. The team used Pirelli tyres and Shell oil and fuel. Giovanni-Battista Guidotti remained as team manager and Orazio Satta Puliga, who had joined the design department in 1938, began the year as chief engineer.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Rising star Juan Manuel Fangio joined Giuseppe Farina while Luigi Fagioli ended 12 years of retirement to replace Consalvo Sanesi, the intended third driver, when he injured his arm during the Mille Miglia.

Fangio drove a singleton 158 to victory in the non-championship race at a wet San Remo on his début for the team, beating Luigi Villoresi’s Ferrari by over a minute.

Alfa Romeo’s next event was the British GP at Silverstone, the team’s first appearance in England. The ‘three Fs’, as they were inevitably dubbed, were joined by local favourite Reg Parnell in a fourth 158. Ferrari withdrew a couple of weeks before the race and Alfa Romeo duly locked out the four-car front row with Farina on pole. Farina, Fagioli and Fangio swapped the lead during the opening 20 laps with Parnell, who had higher gear ratios, in fourth place.

Fangio was running a close second when his oil pipe fractured with eight laps to go, so Farina led home a dominant 1–2–3 with the radiator on Parnell’s third-placed car deranged after he hit a hare.

The opposition had been lapped at least twice.

Fangio squeezed through the crashed cars and was 51.8sec ahead by the end of lap two. He led throughout, lapping the depleted field.

Farina and Fagioli finished 1–2 in Switzerland while Fangio qualified on pole position but retired when running second. The first suggestion that large, normally aspirated engines might be the future came at Spa-Francorchamps, where Raymond Sommer’s 4.5-litre Lago-Talbot led for five laps when the Alfas refuelled. With the 158s requiring a second stop and Sommer running non-stop, the whiff of an upset was in the air before the Frenchman’s engine failed after 20 laps. Fangio led Fagioli home while Farina pitted to check falling oil pressure before finishing fourth at reduced pace.

Fangio led yet another Alfa 1–2–3 in qualifying for the French GP at Reims. Farina led the opening 16 laps before two lengthy pitstops to cure a fuel-feed problem. He climbed back into third position before coasting to a halt on the back straight with nine laps to go.

Non-championship victories followed at Bari (Farina), Geneva, Pescara (both Fangio) and Silverstone (Farina). Fagioli was on course to win at Pescara before his front suspension broke on the last lap; Fangio followed the stricken car as it limped to the finish but sped past within sight of the line when Louis Rosier’s fast-closing Lago-Talbot threatened to snatch victory.

With four points covering the regular team-mates at the Italian GP, Alfa entered additional 158s for Sanesi and Piero Taruffi. Company management appeared to favour Farina and he had an upgraded engine that developed an extra 20bhp in what was now dubbed the type 159. They had meaningful opposition at last as Ferrari finally exploited the full 4.5-litre normally aspirated capacity. Fangio qualified on pole position but it was Farina who made the best start. Alberto Ascari’s Ferrari led for a couple of laps before both he and Fangio retired, the Argentine driver taking over Taruffi’s car until it also broke. Farina continued unchallenged to a victory that clinched the inaugural world title. Fagioli was third while Sanesi, who had qualified on the outside of the front row in a fine fourth place, retired early.

Less than a month later, Farina was injured in a road accident outside Genoa while Fangio, frustrated by ill luck and team orders, returned to Argentina to consider his future.

Go ad-free for just £1 per month

>> Find out more and sign up

Scuderia Ferrari

Alfa Romeo engineer Gioacchino Colombo joined on 1 January 1948 and designed the short-wheelbase Ferrari 125 with tubular chassis and 1,498cc 60-degree V12 engine with a single Roots type supercharger and four-speed gearbox. The original 125 had transverse-leaf independent front suspension and torsion-bar rear axle. It was underpowered and handled badly so Colombo’s assistant, Aurelio Lampredi, reworked it for the 1949 Italian GP with two-stage supercharging, twin overhead camshafts, a five-speed gearbox and – to improve handling – modified rear suspension and a longer chassis. Alberto Ascari won that race and both he and Luigi Villoresi remained as works drivers for 1950. Their entries for the British GP were withdrawn just two weeks before the inaugural World Championship race, The Autocar reporting that ‘there has apparently been the usual disagreement with regard to the amount of starting money to be paid for their attendance. ‘Ferrari arrived late for the following week’s Monaco GP and so missed the opportunity to qualify in the top five positions as these were decided in first practice. Ascari and Villoresi, who had set a time that would have been good enough for second on the grid, avoided the opening-lap chaos at Tabac but Villoresi choose the wrong way around the pile-up on the second lap and stalled. He push-started his car but eventually retired when third while Ascari finished second.

Raymond Sommer drove the works V12 Ferrari 166/F2/50 he had used to win the supporting F2 race but its suspension failed before half distance.

As these cars were no match for the Alfas, technical director Lampredi was already experimenting with normally aspirated designs, the first of which appeared at Spa-Francorchamps where Ascari finished fifth despite an early puncture. His old long-wheelbase chassis was fitted with the atmospheric 60-degree single-overhead cam 3,322cc V12 sports car engine. The renamed Ferrari 275 remained underpowered and lacked the Lago-Talbots’ fuel range.

No supercharged works cars were taken to the French GP, where Ascari and Villoresi shared the Ferrari 275 during practice but the car was withdrawn.

No supercharged works cars were taken to the French GP, where Ascari and Villoresi shared the Ferrari 275 during practice but the car was withdrawn.

Engine capacity was stretched to 4,101cc for the non championship GP des Nations in Geneva and two new 4,494cc Ferrari 375s were introduced at the Italian GP. These had are designed tubular chassis, four-speed gearbox, independent front suspension via wishbones and transverse leaf springs, and a de Dion rear end. Ascari qualified second and led a couple of laps before his engine failed. Villoresi had been injured at Geneva so Dorino Serafini drove the second Ferrari 375 at Monza. He qualified sixth and handed his car to Ascari, who finished second. With Alfa Romeo absent, Ascari completed 1950 by leading a Ferrari 1–2–3 in the Penya Rhin GP at Barcelona to confirm that normally aspirated engines represented Ferrari’s immediate future.

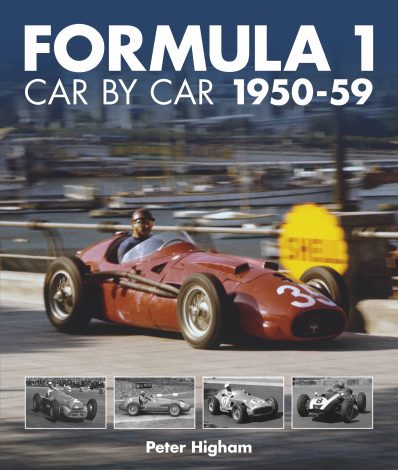

Formula 1 Car by Car 1950-59 by Peter Higham is a detailed history of every car which raced in the first decade of the world championship. Look out for a review coming soon on RaceFans.

You can buy Formula 1 Car by Car 1950-59 directly from Evro Publishing.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

F1 history

- How you rated F1’s 12 sprint races so far – and why two outscored the grand prix

- Alonso set to become F1’s oldest driver for more than 50 years

- From ‘Flying Pig’ to Senna’s heroics: The short, incredible history of Toleman

- From farcical to fantastic: Formula 1’s 14 title-deciding Japanese races ranked

- Benched: The five other drivers who stood down for team mates in last 50 years

bull mello (@bullmello)

13th May 2020, 18:29

Great birthday for F1!

Older than me. :-)

Tenerifeman (@tenerifeman)

14th May 2020, 2:34

Younger than me …. Booo Hoooo

frood19 (@frood19)

14th May 2020, 8:11

Is this a typo?